Your cart is currently empty!

Altered Images

I’m Leia Acos

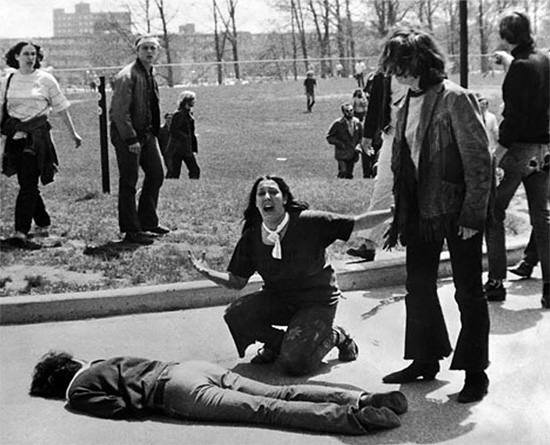

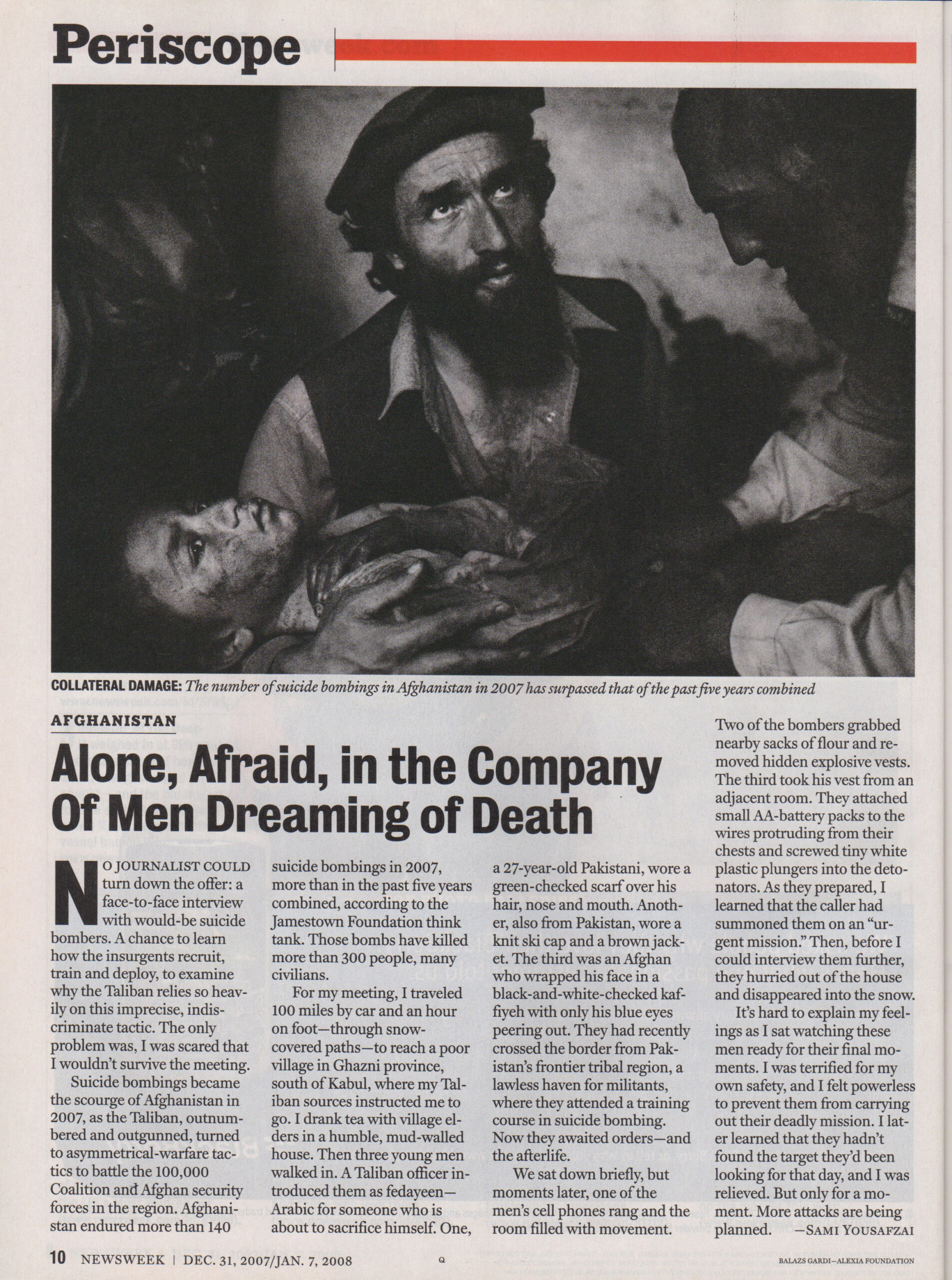

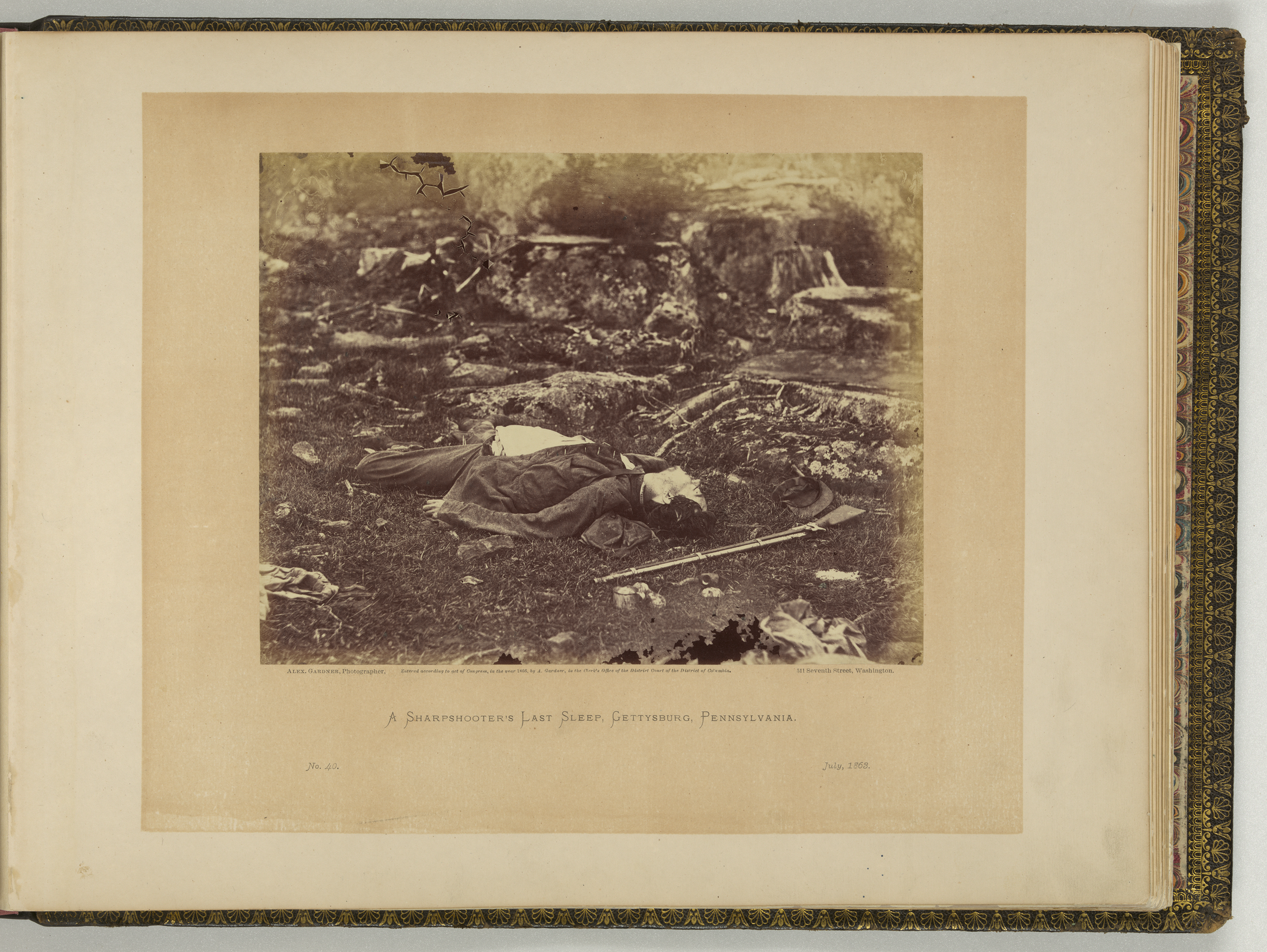

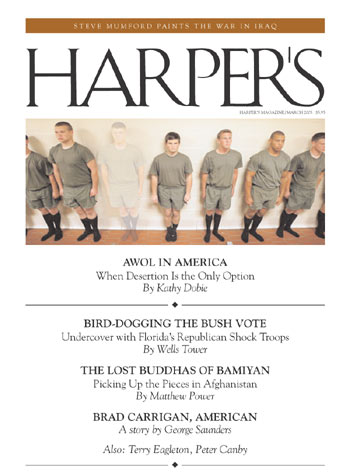

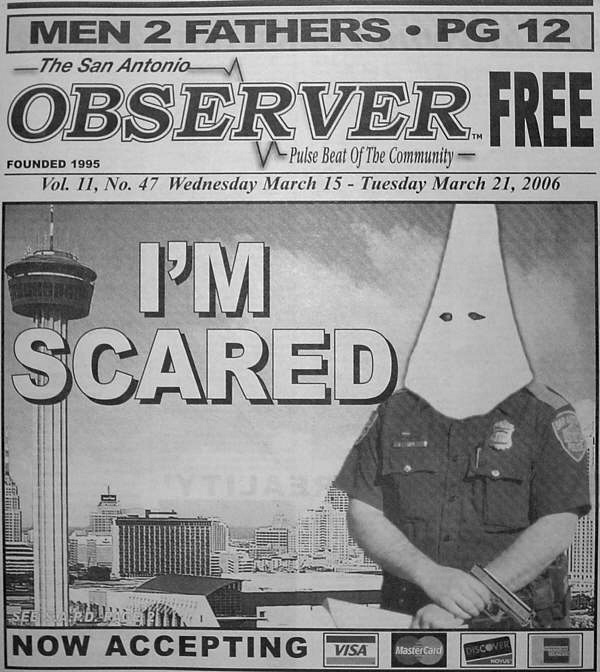

The exhibition, Altered Images: 150 Years of Posed and Manipulated Documentary Photography, was on view at the Bronx Documentary Center from June 20 to August 2, 2015

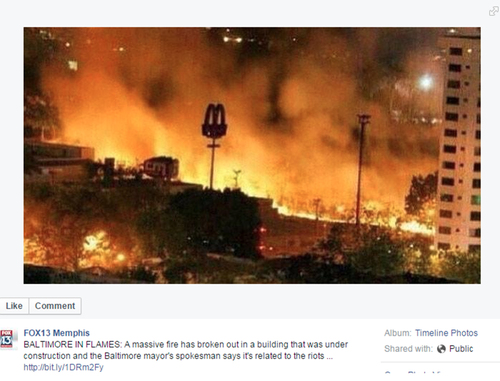

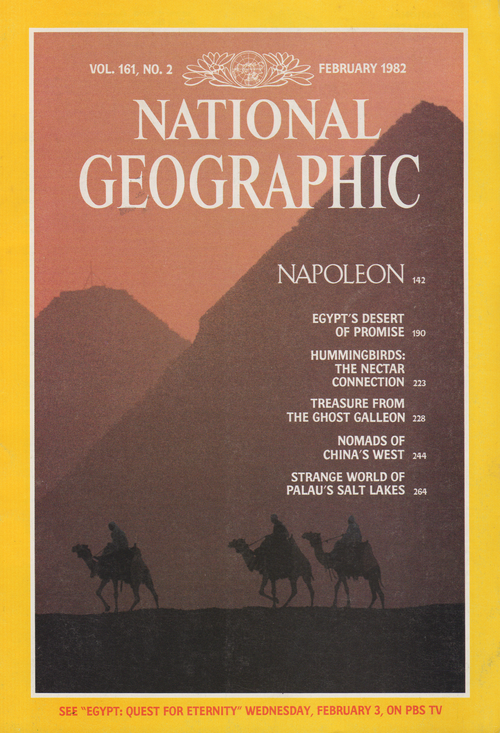

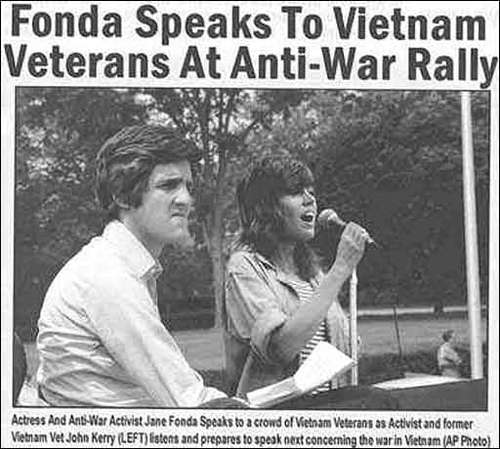

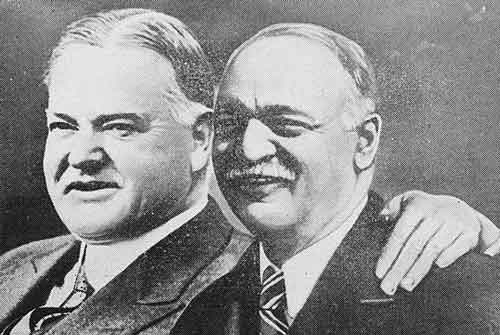

This resource page, researched and created by Bianca Farrow and Mike Kamber, explores disputed images in photojournalism and documentary photography–photos that have been faked, posed, or manipulated.

From photography’s earliest days, a small number of photographers and editors have misled the public. Others have made mistakes in judgment and execution. Regimes have used altered images as propaganda. This exhibition examines prominent cases and ethical documentary practice.

Following WWII, a code of photographic ethics emerged. Experienced photo editors, alert to signs of manipulation, pored over negatives and contact sheets. Today, bankrupt and cost-cutting media publications have laid off thousands of photo editors and staff photographers.

Many untrained and poorly paid freelancers—each with the power to alter a scene at the click of a mouse—have largely replaced them.

Editors with little or no photo experience post images to the Web in seconds. Corporations, political campaigns, and regimes around the world flood the Internet with doctored photos. A new barrage of altered images is being presented to the public, and we are faced with a crisis of credibility.

Click here to learn more about this image.

Documentary photographs and photojournalism must be accurate representations of the scene before the photographer’s camera–without alteration. If the public is to have faith in the integrity of the image before them, and by extension the media, images must be taken and published in a forthright manner. Broadly speaking, the photographic alterations in this exhibition fall into three categories.

STAGING:

Photographers must not direct a subject or use the photographer’s presence to significantly alter an event. History unfolds in real time, not at the desire of the photographer. Portraits are the exception to this rule and should be clearly identified as such. One does not pay a subject: Doing so radically changes the nature of information gathering and destroys the ability to capture reality.

POST-PRODUCTION:

Post-processing adjustments, whether in the darkroom or in Photoshop, are generally used only to represent the reality of the scene accurately; for instance, to brighten a sky or darken a photo taken at dusk. Objects must never be added or removed from an image in post-production.

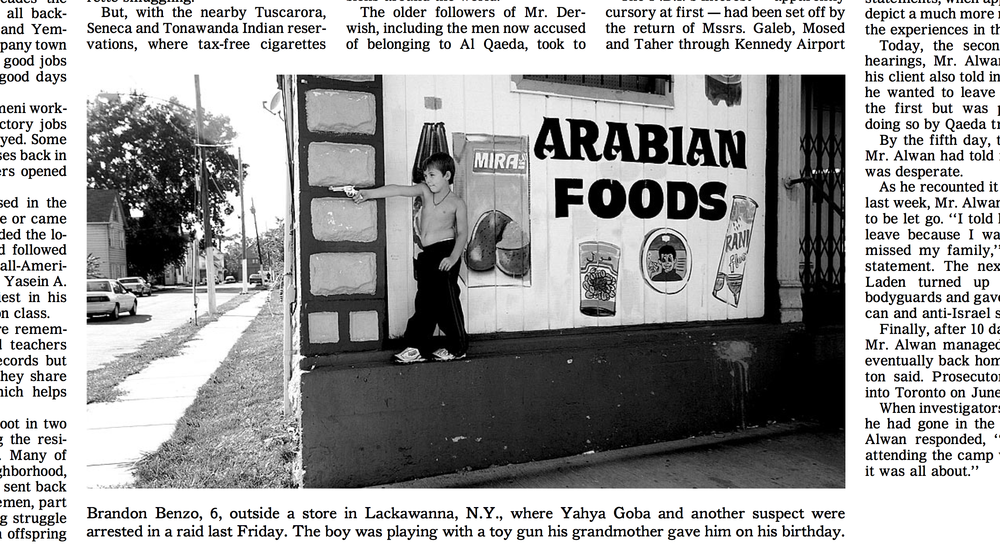

CAPTIONS:

The context in which a photo is shown—the information published with it—is often as important as the image, sometimes more so. Does it matter that Robert Capa’s iconic photo from the Spanish Civil War was not taken when and where the caption stated? For history, and for the viewer, it matters very much.

Images

Videos

Altered Images in the Press

Altered Images is made possible, in part, by the Phillip and Edith Leonian Foundation, the Ford Foundation, the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature, by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the city council and by City Council member Maria del Carmen Arroyo.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance from Associated Press, European Press Agency, The New York Times, The Washington Post, the South Dakota State Historical Society, Art Resource, International Center of Photography, Getty Images, and the San Antonio Public Library.